Uncommon Service is a “what to do and how” kind of book. If Atomic Habits is a what/how book for the person then Uncommon Service is one for service businesses.

It’s organized into four parts:

One: The tradeoffs. To have uncommonly great service, a business must make tradeoffs. Importance requires attention – and there’s an opportunity cost to that attention. In Unreasonable Hospitality, Will Guidara writes about the front-of-house staff that aims to create “legendary” moments for the guests. They Google the guests. They run out at the last minute for just the right gift. They go above and beyond above and beyond.

But they don’t shine glasses, clean tables, or sweep the sidewalk. They don’t help with any of the hundreds of tasks that need doing every single night. That’s a tradeoff.

The LinkdInfluencer scoffs, be the best. But businesses that dig deeply into customers’ jobs find there are things the customers want more than others. Your customers want tradeoffs.

Two: Things cost money. Uncommon service isn’t free.

Customers could pay more and get more. Premium services like Disney’s Backstage Magic tour and The Four Seasons work this way but these opportunities are limited. Most businesses cannot simply charge more.

Instead, most businesses must find holistic solutions. Exceptional service leads to more word of mouth and less marketing spend. Specialized service leads to better processes and less loss or more gain. When Publix employees walk customers to requested items – rather than tell them the aisle – does that increase sales and decrease theft? Certainly.

Few businesses can claim it cost more and it’s worth it, but all businesses can think creatively about how to offer more and how to pay for it.

Three: A business’s team reflects a business’s tradeoffs.

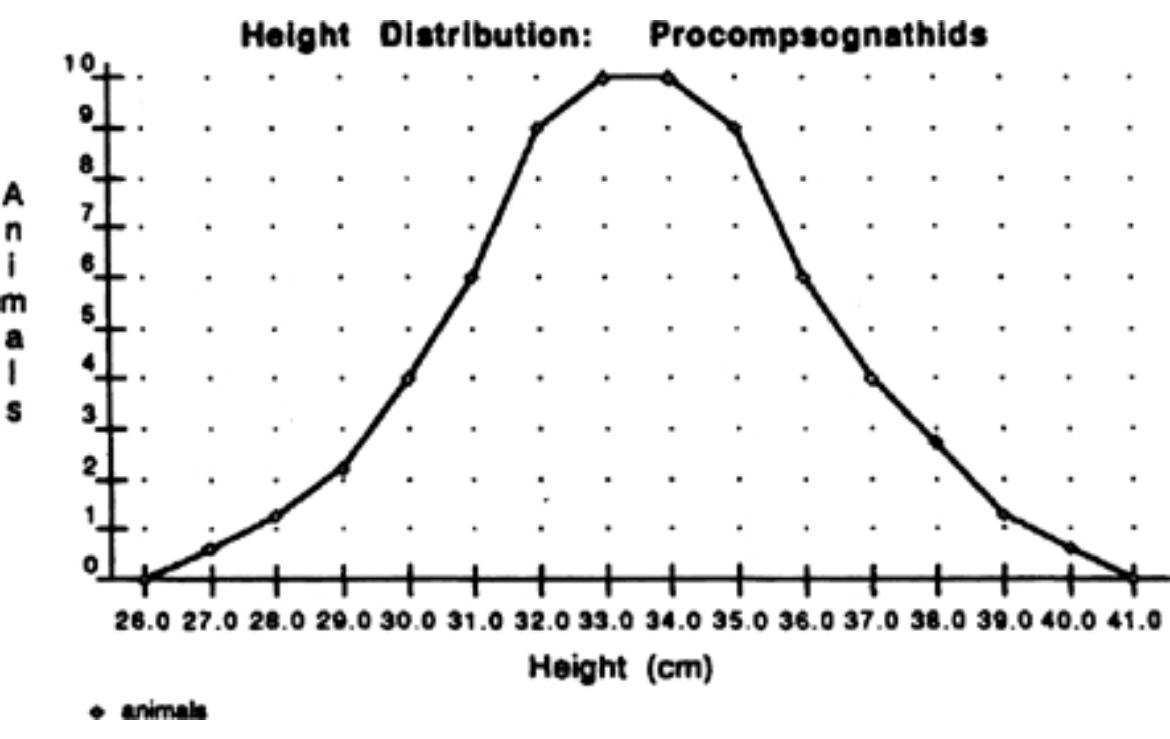

Florida has a lot of mom-and-pop pool cleaning businesses. Our neighbor likes reports that detail the pH, chlorine, and salt levels. For him, the JTBD is visual and numerical.

But most cleaners want to show up, clean, and move on – while listening to whatever on Bluetooth headphones.

So the business owner makes it easy for their employees. Rather than have the cleaner communicate with the customer, they communicate with the office that prepares the report. Cleaners take a few photos, report some numbers, and move on. The office makes it look as nice and tidy as the pool.

(Alternatively, a business can try to hire people rather than design the system. We write a lot about that at Daily Entrepreneur.)

Four: Prepare the customer. The authors suggest service businesses imagine they are manufacturers. In ‘goods’ businesses customers don’t wander around the plant, inspecting machinery, and tinkering. No – and they shouldn’t do that in a service business.

But customers are part of the experience: they have varied expectations, arrive at different times, and spend different amounts. They are “locally logical”: what makes sense to one will not make sense to another.

Like employees, a business has two options. They can change the system for the people or change the people for the system.

We’ve written about financial stakeholders. An investor is only as good as their capital base. This is part of Warren Buffett’s persona: he draws people aligned with his approach. He picks the people for the system.

But not every business can filter their customers. In those cases, they must focus on the customer’s experience. How can a business operator systematize the times they bend over backward?

Historically Harvard Business books run dry with too much theory or too specialized examples. This book did not. It was uncommonly good, fast, and helpful.

Notes. Never Split the Difference addresses tradeoffs well. Both Never Split… and Uncommon Service are recommended by Bob Moesta.