In the first post we jumped off with the idea that the S&P500 is an unbalanced collection of stocks. The top five companies, noted Carl Kawaja, generate 22% of the earnings, so why not only ‘bet on’ the best?

This led to thinking about predictability. Chess is easier to predict than my morning pickleball game. Michael Mauboussin wrote a wonderful book about predicability as framed by skill and luck.

Think about events, Mauboussin explained, as a continuum: from the least skill activities (roulette) to the more skill components (stock markets, hockey, football) to the mostly skill components (basketball, chess). An event’s predictability slides as the skill portion of an outcome increases.

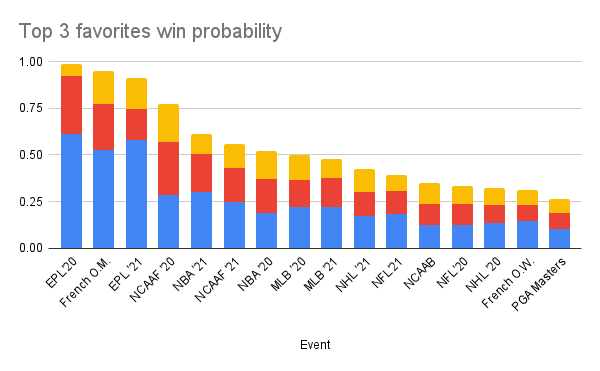

Here is how sport predictions look.

On the Wharton Moneyball podcast the hosts often talk about betting the favorites or the field. Bettors in events toward the left of the graph are better off betting favorites and events toward the right taking the field.(1)

With two years of data (sorta) it seems that some sports are more predictable (more skill, less luck) than others. Here’s how Mauboussin ranked sports, starting with most skill based: NBA, EPL, MLB, NFL, NHL.

Contrast that with our (sorta) model: EPL, NBA, MLB, NHL, NFL. That’s a pretty good match!

How to use this: to consider if our predictions are more like the NBA or more like the NFL and it’s “any given Sunday” ethos. In NBA-like situations there are a few big issues (players) that drive the results. In NFL-like situations there are more chances for odd bounces (fumbles), subjective decisions (pass interference), or fortuitous circumstances (turnover-worthy pass attempts).

Nothing in real life will be like these sports, but to have a good analogy is a good decision making tool.

–

(1) “Buying good things can’t be the secret to success in investing,” wrote Howard Marks), “It has to be the price you pay. It’s not what you buy, it’s what you pay. There’s no asset so good it can’t become overpriced.”