Note, this was originally posted on Medium. I’m reposting here for my own ease of linking.

I feel quite silly about how this revelation occurred.

I’ve written about how imitation (among other things) is a great way to start as a writer.

- Malcolm Gladwell said, “with my own writing. I began as a writer trying to write like William F. Buckley, my childhood hero. And if you read my early writing, it was insanely derivative. All I was doing was looking for models and copying them.”

- Felicia Day suggested we not mock fan fiction because it’s a good stepping stone to bigger and better things.

- Stephen King wrote:

When you read what someone has written, the style rubs off on you. It’s inevitable.

This makes sense, but applies to the domain of style. What if it was applied to the domain of process?

How to write a book like Ryan Holiday

I like reading Ryan Holiday’s words. My favorite book is The Obstacle is the Way, but his blog posts are generally good, and his monthly emails about books always give me something to read. I’ve liked his podcast interviews so much I’ve shared my notes; here, here, and here. In all this he’s shared (multiple times) his process for writing a book.

Why don’t I copy that?

As I compiled this list, I realized that book writing isn’t linear. This reminded me of Steve Callahan, a man lost at sea for 76 days. Callan lived because he juggled the things he needed. Food, sleep, water, food, food, sleep, water, repairs, etc. There was no left-to-right sentence about how to stay alive, and there is none to write a book.

But there are some things I can do.

1/ Read widely.

Every author says to read widely, but Holiday’s ethos appealed to me most of all:

“collect what you’re naturally drawn to, so you start to recognize patterns and interests, which gives you direction for what you should write next. It’s a great cure for writer’s block.”

Read whatever I want? Stop, this feels like cheating.

Well, almost. Holiday’s reading lists are almost all non-fiction, with lots of biographical work. The books he’s written reflect that.

This means I won’t write a book like Mary Roach (not that I could achieve her style or substance) who rarely uses secondary material (books) or Malcolm Gladwell. They talk to scientists, read journals, and interview experts. I’ll follow Holiday’s path for one reason, it’s easier. To paraphrase Seneca, “books are never too busy to see you.”

Okay, read whatever I want. Does the medium matter?

When Lifehacker asked Holiday about his favorite gadget, he said physical books are “the perfect technology.” Michael Mauboussin (another great writer) says he remembers things better out of physical books. Sounds good to me.

Conclusion: Read a lot of nonfiction books. Choose physical over digital.

2/ The gear.

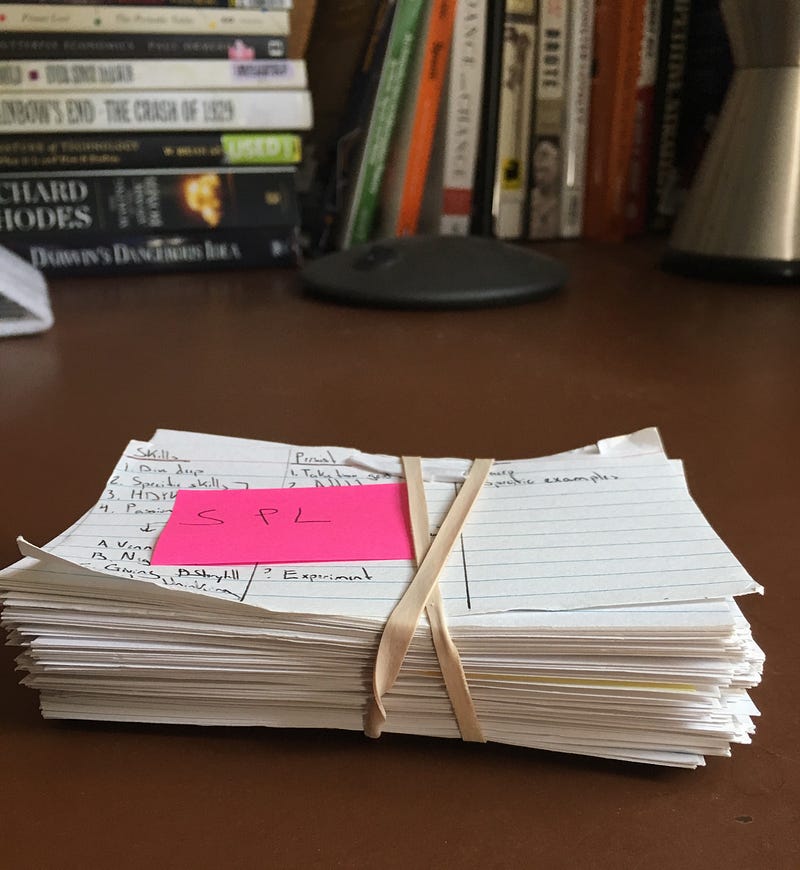

“If I have a thought, I write it down on a 4×6 notecard and identify it with a theme–or if I am working on a specific project, where it would fit in the project.”

Holiday’s system is a perfect example of a theory I have that “the gear doesn’t matter.”

Casey Neistat is always being asked what gear he uses, and always says that gear doesn’t matter. B.J. Novak said he uses notebooks and Microsoft Word. Warren Buffett doesn’t have a computer in his office. Holiday uses notecards, Google Docs, and Word.

What matters more than the gear is the work. If you fret over the gear, or wait for the right gear, or search for the best gear you lose time — and time is the input for work.

Gear only matters in that it’s good enough. Notecards are, says Holiday.

“being able to physically arrange stuff is crucial for getting the structure of your book or project right. I can move cards from one category to another. As I shuffle through the cards, I bump into stuff I had forgotten about, etc.”

Notecards spread on your desk are stepping-stones. They let a writer flit from one topic to the next. Other writers like Sebastian Munger and Anne Lamott both note that it’s not ‘writer’s block’ so much as ‘writer’s chasm.’

The notecards solve this problem. They keep you moving.

When Chris Fussell was an assistant to General Stanley McChrystal he said his goal for the general was “no locked doors.” That is, Fussell anticipated what McChrystal would need next and do it before he needed it. Notecards are what the book needs next and having enough of them keeps the writing going.

Okay, so the gear doesn’t matter past a very basic point. Except for this:

Holiday is always mentioning this water. What the hell, I’ll buy some too.

Conclusion: Notecards are a good enough system. It’s about the ends, not the means. Plus, stay hydrated.

3/ Have a plan and something to say.

An author friend recently told me that he’d written 115,000 words for the book he was working on; a book that contractually was only going to be 60,000 words. And worse, it was only just now that he’d really figured out the thrust of the book…It almost broke my heart.

A plan. This is much harder. Where am I going? What am I trying to accomplish. For starters, I’m not doing this for money.

No, I just have something to say. That’s good, writes Holiday.

My theory on writing books is that you have to have something you really must say. Anything less than that and you’re doing it for the wrong reasons.

When Holiday suggests ‘have something to say’ it reminds me of Peter Thiel’s encouragement that entrepreneurs look for secrets. Find things that people want but are not easy or impossible to provide.

A book could be that.

- When Phil Knight founded Nike, he found a secret.

- When Apple released a touchscreen smartphone, they found a secret.

- When J.K. Rowling wrote Harry Potter, she found a secret.

I imagine Thiel’s Secrets are like coal seams. They’re all around us. Some are big, some small. It takes a bit of digging and work, but you could find one. Ideas are like that too.

Conclusion: Focus on the ‘thing you want to say.’

4/ Know it’s going to be hard.

10:06am: You’re starting to think that maybe you don’t know this as well as you thought you did. Did you not prepare enough? Is the idea not good enough? Is this ever going to be anything? What the fuck, what the fuck?

I’m not sure why, but knowing something is going to be hard seems to be better than thinking it will be easy. When I ran a marathon, this was the case. When I had kids, this was the case. Starting this book, it’s good to know this is the case.

The difficulty validates the work.

Another theory I have is that dream jobs are BS. I think Holiday agrees:

Creative work isn’t about pleasure. It’s not always fun. It’s about reaching something inside yourself–something that society and everyday life make extraordinarily difficult.

Austin Kleon was once asked what it’s like to be an artist (full-time). He said not all of a dream job is dreamy. It’s still a job.

Holiday also seems to have some self-doubt (What the fuck, what the fuck?). Me too. When I tell people I’m a writer it feels like being in the wrong cage at a zoo. I’m a monkey who ends up with the lions. Oops, sorry I’m here, please don’t eat me.

Conclusion: Frame writing a book like a challenge or game. Doubters give me extra energy, embrace the real ones or manufacture fake ones.

5/ Make commitments

the plain reality is that books are hard to write, and as you trudge along you’ll make a million excuses.

Oh, ho ho ho. Do I have excuses. First I have a confession. I’ve actually used Holiday’s notecard system before.

Those notecards led to 20,000 words, but no book. This is the hardest decision yet.

Conclusion: Tell anyone who asks what I’m doing. Commit to a finish date.

6/ Have a routine.

Dress in the same old clothes as always, go downstairs.

Holiday shared his full routine:

What the routine does, — I’m guessing — is remove choices. You don’t have to decide what to do. To put it another way, that blob of gray material between your ear doesn’t get to choose a quick hit of Twitter. (Which is never quick, and never scratches the itch).

I created a routine accidentally. When I decided to post three days a week at TheWaitersPad.com that began a routine that is pretty well entrenched. Malcolm Gladwell said his work at the Washington Post did this for him. My little blog and his big paper experience are widely different — except for this. They both established the habit of writing.

Conclusion: Create my own routine.

7/ Exercise.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve rushed home from a run and shouted, “Nobody talk to me, I have to write this down!” while I dripped sweat all over my computer or my note cards as frantically tried to get it down before I lost the thought.

Holiday’s not the only one to finish a run with an idea. Beethoven used to walk around town with loose papers and a pencil to jot down ideas. Dickens would get ideas on his daily walks too. In fact, writes Mason Currey, many people who are writers are also walkers.

Holiday runs. Malcolm Gladwell runs. Cal Newport runs.

Conclusion: I’ll keep running (and thinking).