Supported by Greenhaven Road Capital, finding value off the beaten path.

The book Ike’s Bluff by Evan Thomas covers the Eisenhower presidency, 1953-1961. Thomas is bullish on the Kansanian, making the case that Eisenhower played the game of president well. That may be the case, but while I’ll never be the “Supreme Allied Commander”, Eisenhower’s decision-making principles work for grunts too.

These are only partial notes. This book was fantastic and along with Minute to Midnight and Dan Carlin’s podcast on the Cuban Missle Crisis, an excellent expedition into recent American history.

- You can be a thing or you can do the thing.

- Education isn’t about a particular place or person.

- Smile and take their best punch.

- Prompt good arguments.

- Play games you can win.

- Consider the opportunity cost.

- Question the incentives.

- Beware forecasters with partial information.

- Don’t just do something, sit there.

- What matters that you haven’t (or can’t) measure?

…

Be or do.

“Eisenhower disliked strutters and desk pounders, especially after working for General MacArthur in the 1930s. He preferred to operate by indirection and behind the scenes.”

Eisenhower was criticized for not cheerleading from his pulpit but that wasn’t his chosen path. He focused more on doing than being. This was true for fellow military man John Boyd who coined our phrase ‘be or do’. You can be a thing, Boyd would tell the people who worked with him, or you can do a thing.

…

DIY MBA.

“His de facto graduate school was the three years he spent in the early 1920s under the command of General Fox Conner, a genius soldier-scholar, in a remote outpost in the Panama Canal Zone…With Conner, Eisenhower read Plato, Tacitus, and Nietzsche, among other philosophers and thinkers.”

Education isn’t a place or a person. Education is a perspective. Are you going to learn or not? Eisenhower downplayed this to others but he was an eager learner.

Meb Faber is learning by doing by investing in startups. Ben Carlson suggested learning by investing in general. Seth Klarman said he probably learned more during his time at Mutual Shares than at business school. Eisenhower was furiously curious.

“As a boy, he had become so entranced by volumes of Greek and Roman history that his mother, irked that he was neglecting his chores, locked the books in a closet. Eisenhower found the key and read while she was off doing errands (another of his heroes, or in this case an antihero, was Hannibal, a magnificent loser).”

…

Smile and take their best punch.

“The famous smile, Ike told his grandson, David, came not from some sunny feel-good philosophy but from getting knocked down by a boxing coach at West Point. The coach refused to spar anymore after Ike got up off the mat looking rueful. “If you can’t smile when you get up from a knockdown,” the coach said, “you’re never going to lick an opponent.””

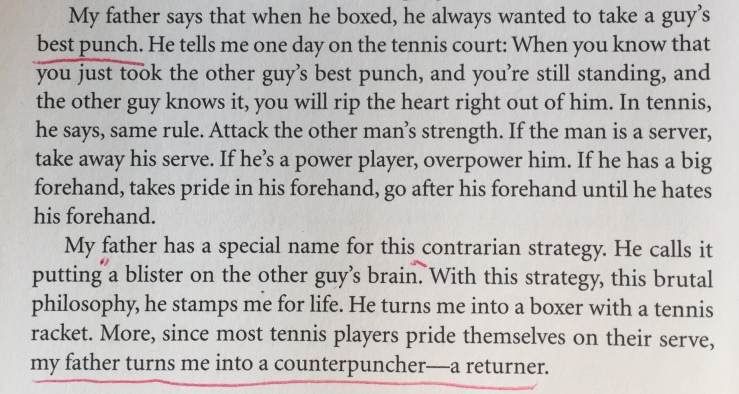

When Andre Agassi started playing tennis his dad said that he needed to learn to take the other guys best punch, to put “a blinster on the other guy’s brain.”

…

Argue well. Of all the things in the book, this ability surfaces again and again.

“Eisenhower was cagey, and he could be a provocateur, jumping into discussions to stimulate debate. He wanted to hear all sides, even if that meant arguing with himself.”

“A few days later, in a memo to the Army Chief of Staff, Ike suggested “the use of one or two atomic bombs in the Korea area, if suitable targets can be found.” The suggestion seems offhand, almost cavalier, but it could well have been made in typical Eisenhower fashion, as a prompt to debate.”

“He had an uncanny ability to enter directly and forcibly into a debate without squelching it,” wrote Robert Bowie, the State Department’s policy planning director.”

To argue well is to discuss ideas without ego. It can be uncomfortable noted Dan Egan but it’s a good way to make decisions. Marc Andreessen and his partner Ben Horowitz seem to have followed Ike’s lead. Marc said he takes the other side of Ben’s ideas even if they’re great.

…

Play games you can win.

“Never get in a pissing match with the skunk,” Ike told his brother Milton, who had pressed him to take on McCarthy by name.

McCarthy was a thorn in Eisenhower’s side. Rather than fiddle with it, it fell out on its own. Basketball teams know you can’t beat a team at their own game. Or, as Charlie Munger said, stay in your circle of competence, “If you play games where other people have the aptitudes and you don’t, you are going to lose.”

In Korea and Vietnam, this idea became a battle.

“Eager to restore their dignity after the shame of Nazi occupation in World War II, France clung to Vietnam, its longtime colony, despite a nationalist revolution led by Ho Chi Minh, who had studied Marxism as a student in Paris. The French wanted to draw the Vietminh, as the Communist rebels were called, into a conventional set-piece battle. The Vietminh were everywhere and nowhere. Talking to a Western reporter in 1952, the Vietminh top general, Vo Nguyen Giap, pointed to a dirt path and said, “Our boulevards.” Smiling, Giap asked, “In our war, where is the front?””

In our post on John Nagl we looked at the lessons of jungle warfare and Eisenhower knew them back then. The jungle, Eisenhower said, would “absorb our troops by divisions!”

…

Opportunity costs. Eisenhower called it “the great equation.”

“The jet plane that roars over your head costs three quarters of a million dollars. That is more money than a man earning ten thousand dollars every year is going to make in his lifetime…Now, here’s the other choice before us, the other road to take—the road of disarmament. What does that mean? It means for everybody in the world: butter, bread, clothes, hospitals, schools—good and necessary things for a decent living.”

“We pay for a single fighter plane with a half a million bushels of wheat. We pay for a new destroyer with new homes that could have housed more than eight thousand people.”

Knowing these costs is hard. You have cast a wide net, said Rory Sutherland. Opportunity costs exist for books, said Jeff Annello, investments said Marc Andreessen, and work said Ryan Holiday.

…

Incentives. To go along with opportunity costs, Eisenhower understood the incentives of the people he worked with. Leaders who aren’t owners prefer more to less.

“Eisenhower had a healthy skepticism about the grandiose schemes of the military. He knew how the top brass used worst-case scenarios to frighten their civilian masters into spending more on unnecessary new weapons systems and pet boondoggles.”

““I’m damn tired of the Air Force sales programs,” he said. “In 1946, they argued that if we can have seventy groups, we’ll guarantee security for ever and ever and ever.” Now they had come up with this “trick figure of 141. They sell it. Then you have to abide by it or you’re treasonous.” One member argued that the air force knew better than the politicians how to measure its needs. “Bunk,” Eisenhower scoffed. He knew the Pentagon “as well as any man living,” he said, and he knew how the people who worked there routinely overstated their case.”

Ben Falk saw mangled incentives in the NBA and Eric Maddox saw them in Iraq.

…

Forecasts for war.

“During the Korean War, President Truman had invoked a document called NSC 68, prepared for the National Security Council, calling for a massive arms buildup to face the Communist threat. NSC 68 warned of a “year of maximum danger,” when the Russians would have a hydrogen bomb and the means to deliver it. Ike regarded “target dates” as “pure rot,” a “damn trick formula of ‘so much by this date.’ ”

“Eisenhower had been more realistic than the jittery Pentagon planners who in the early days of the Cold War had predicted that the Red Army could—and would—roll virtually unimpeded to the English Channel, and even predicted the day: January 1, 1952. According to Army G-2 (intelligence) estimates, the Soviets could overrun Western Europe in two weeks. Writing in the margin of one such estimate in 1948, Ike jotted, “I don’t believe it. My God, we needed two months just to overrun Sicily.””

Part of the reason Eisenhower knew the numbers were wrong was that of the pictures he saw. The U2 spy plane provided the best intelligence he could get on Russia – or any part of the world, including his own farm. Good forecasts take a lot of work. Eisenhower might have been a Superforecaster.

…

Don’t just do something, sit there.

“Eisenhower was “an expert in finding reasons for not doing things,” recalled Andrew Goodpaster, his staff secretary and the adviser who probably knew him best.”

Sometimes the best action is no action. In the early days of NASA, the default was to do nothing. Gene Kranz wrote, “the first rule of flight control is if you don’t know what to do, don’t do anything.” Busyness, wrote Cal Newport, is not a proxy for productivity. Investor’s trail returns because of doing too much.

…

What matters that you haven’t measured?

“Ike was a believer in what he called the p-factor—psychology, propaganda, persuasion.”

“He was seeking opportunities to, as he liked to say, “win World War III without having to fight it.””

For this ideas, check out our week of posts on Rory Sutherland.

Thanks for reading. Want more? Sign up here: http://eepurl.com/cYiwTP.

[…] Dwight Eisenhower knew this too, and so did his brother who told him to “never get into a pissing match with a skunk.” Ike’s military history and experience directed him away from fighting in Vietnam and Korea. It also guided him in the mano a mano battles on the hill. […]

LikeLike

[…] archetype of argument might be Dwight Eisenhower who kept his inner circle running in circles. Ike never tipped his hand, especially in cards, about […]

LikeLike

[…] Catmull wrote, Jobs would float out ideas just to see what people would say. Dwight Eisenhower, we saw, did this […]

LikeLike

[…] like Ike, we can find reasons for not doing things. So we can ask: am I doing something that matters or am I […]

LikeLike