Dan Coyle (@DanielCoyle) joined Brian Johnson (@_Brian_Johnson) on the Optimize podcast to talk about talent. Coyle is the author of The Little Book of Talent and The Talent Code. In this episode the pair breaks down the different ways to grow talent (note, talent is grown, not genetic). As always, the entire interview is good, here is our table of contents.

- Community.

- Biology of it.

- Deep practice (with a bear).

- Lunchpail mentality.

- How Dan Coyle did it.

- Practical tips.

Community.

Coyle’s book, The Talent Code begins with a question, “How does a penniless Russian tennis club with one indoor court create more top-twenty women players than the entire United States?” That, is a good question.

Coyle went on to investigate what that club did that others didn’t. The details are many (some of which we’ll get into below) but one was the community.

These “talent hotbeds” aren’t atypical. Austin Kleon writes this in his book, Show Your Work:

“There’s a healthier way of thinking about creativity that the musician Brian Eno refers to as “scenius.” Under this model, great ideas are often birthed by a group of creative individuals—artists, curators, thinkers, theorists, and other tastemakers—who make up an “ecology of talent.” If you look back closely at history, many of the people who we think of as lone geniuses were actually part of “a whole scene of people who were supporting each other, looking at each other’s work, copying from each other, stealing ideas, and contributing ideas.” Scenius doesn’t take away from the achievements of those great individuals; it just acknowledges that good work isn’t created in a vacuum, and that creativity is always, in some sense, a collaboration, the result of a mind connected to other minds.”

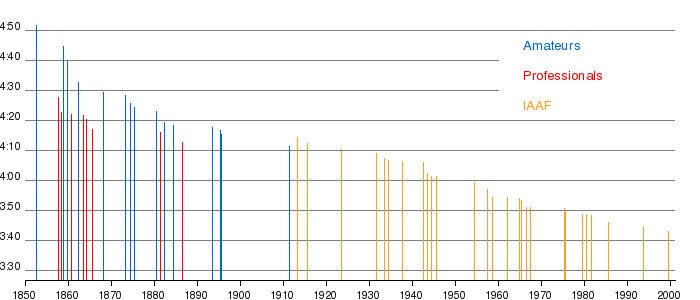

Coyle’s theory is that people need to at least see what’s possible. He mentions the fall of the four minute mile. That is, once Roger Bannister ran a mile in less than four minutes, other people did it too. I’ve heard that story too, but there’s more to it than just that.

You see, mile times had been decreasing for a long time. It wasn’t that people suddenly realized they could be faster, they knew that.

What accelerated the change was that more people actually saw faster running. In the 1930’s and 40’s, videos of runners were shown in theaters and schools. Video’s like this one.

Coyle suggests that communities show other people what is possible. At the Russian tennis club, only 1 person succeeded. In the next cohort, 4 made it big time. Then 6. When tennis players in Russia saw one of their own succeed, they began to do it at a faster rate as well. Coyle calls this “filling your windshield.” It’s keeping the people you want to be like, in your view.

Malcolm Gladwell wrote about this vis-a-vis Jamaican sprinters.

“So why are the Jamaicans so good? There are many reasons, but the simplest is that the effect of peers on high performance are REALLY strong. In Jamaica, EVERYONE sprints. There are 20 heats in the 100-meter regional championships. And because everyone sprints, and the average quality of sprinting is so high, everyone’s expectations are raised accordingly. The psychological ceiling on elite performance if you are a high school sprinter in Kingston is, like, a foot higher than if you are a high school sprinter in America.”

Simon Rich said he wants to be around people smarter than him and feel like he’s barely keeping up. Tim Ferriss volunteered so that he could be around people smarter and more connected.

If you want to get better at something, you should probably be around people who will push you to be better – in Russia or anywhere else.

How this talent thing works, biologically speaking.

Talent, says Coyle, is the ability to do something.

Jump ahead to the 1:00 mark of this video. The question being answered is, “why do speeds increase for myelinated axon?”

Coyle describes myelin as “insulation around a wire that prevents the signal from leaking out.” Certain forms of practice build up myelin. More myelin, faster  signal. Faster signal, better performance. For Coyle, this was demonstrated when he saw Tiger Woods do this – and Coyle wanted to too.

signal. Faster signal, better performance. For Coyle, this was demonstrated when he saw Tiger Woods do this – and Coyle wanted to too.

And he did it! After a few intense minutes a day for eight months I was able to finally do it,” Coyle says. To build these myelin superhighways, you have to practice the right way, and that means deeply.

Deep practice.

Okay, knowing the biology is good, but how do we actually get better at something? The key, is deep practice.

Coyle begins by noting that we should figure out what practice is. We say eat and that can mean a lot of different things. So too for practice.

The type of practice Coyle courages has a certain look. “I’ve noticed that people in the sweet spot,” Coyle says, “have a facial expression that looks like Clint Eastwood.” But besides this guy, what should practice look like? Before we get into it, let’s apply a tool we learned form Joshua Foer. Foer noted (and wrote about) how we remember things. If we can attach a wild image to something, we’ll have a better chance of remembering it. Foer explains:

The type of practice Coyle courages has a certain look. “I’ve noticed that people in the sweet spot,” Coyle says, “have a facial expression that looks like Clint Eastwood.” But besides this guy, what should practice look like? Before we get into it, let’s apply a tool we learned form Joshua Foer. Foer noted (and wrote about) how we remember things. If we can attach a wild image to something, we’ll have a better chance of remembering it. Foer explains:

“The secret to success in the names-and-faces event—and to remembering people’s names in the real world—is simply to turn Bakers into bakers—or Foers into fours. Or Reagans into ray guns. It’s a simple trick, but highly effective.”

When he talks with James Altucher, Foer says that he images Altucher as “I’ll touch her” and him acting like a creep. We can do this too!

Our image for deep practice will be a bear slowly looking through a telescope. It works best if you come up with your own bear, but the internet – of course – has plenty of bears with telescopes.

The bear.

If you succeed more than 80% of the time, says Coyle, the task at hand is too easy. If you succeed less than 50% of the time, it’s too difficult. Like the story of Goldilocks and the three bears, there is a “just right” range of practice.

Steven Kotler said that we can think about improving in small steps. You don’t need to try something twice as hard, instead aim for a 4% improvement. Coyle compares it to a hockey player or figure skater who occasionally falls down. That’s the zone we want to be in.

Go slow.

Coyle mentions implicitly that deep practice is often slow practice. In one instance he talks about Claire learning the clarinet. She moves her fingers so slowly that she feels her mistakes Coyle explains. Later he references this video of Lebron James and Hakeem Olajuwon. This is the most boring video of two of the greatest basketball players ever made.

And for good reason! You have to move slowly to learn new movements.

It make sense that Steve Martin, our grandfather for deep practice, said that he would play a banjo record at a slower speed than normal so he could pick along.

Examine closely, and then widely.

Look at the basketball video again. First Lebron learns where to catch the ball (high/low, near/away from his core). Then where to step. Then dribble. Eventually he puts those sequences together. Then he does it with someone guarding him. People build talent the same way kids build Lego castles – one piece at a time.

Coyle uses the analogy of construction zone and arena zone work. In the construction phase you spend time building, in the arena zone you put it all together. Each of these parts, Coyle says, are important to get things right.

Brett Steenbarger suggested this same – zoomed in, zoomed out – approach to creativity. Steenbarger uses the terms analyze and synthesize. First you dive deep into an idea, then put together what you find. Our bear looks through the telescope at a single star, then lowers it to look at the a constellation.

We can also think about the practice of practice. “These guys all approach learning as a craft, as a pattern, as a system,” Coyle says. That means that getting better at practice is important too. Something else that Coyle has noted as important; a lunchpail mentality.

Lunchpail mentality.

Coyle retweeted this:

Successful people work really hard, Coyle says. He quotes, Michelangelo, “If you knew how much work went into it, you would not call it genius.” It’s hard work.

Michelangelo, Coyle says, worked for stone masons early in his life. He learned how to work with a chisel before he could write. He apprenticed with artists. It was a slog.

“They’re not waiting for inspiration, that’s for the amateurs,” Coyle says.

In Do The Work, Steven Pressfield writes:

“Stephen King has confessed that he works every day. Fourth of July, his birthday, Christmas. I love that. Particularly at this stage—what Seth Godin calls “thrashing” (a very evocative term)—momentum is everything. Keep it going. How much time can you spare each day?”

That’s not what it looks like though. There are more of highlight reels than practice sessions. But the reality is the opposite. There is a lot more practice, than there are highlights.

Carol Leifer spoke and wrote about bombing as a comedian. It happened a lot. You don’t get that when you look at her IMDB profile. It’s filled with credits for some of the greatest shows ever. That took work to get there.

Brian Koppelman said that he had to work on Solitary Man everyday. If he didn’t then it would feel to him like he wasn’t moving the project forward. Even if it was something small, he did it. (Koppelman went so far as to write on his shoes as a reminder).

How Dan Coyle did it.

Coyle is no stranger to the process. Starting out he wanted to be a sports writer, “so I would go to the games and I would come home and pretend I was on a deadline and write up the story on the game I just watched as if I worked for a paper.”

Malcolm Gladwell recently advised something similar. Gladwell said, work for a newspaper. It will force you to write (a lot!). It will force you to hit deadlines. It will develop your skills of asking question. Jason Zweig spoke about the tutelege and institutional memory at papers. Each of these things fits perfectly with the construction and arena example of how we can build skills.

Practical tips.

A lot of the talk of talent and success is abstract, but Johnson and Coyle end the interview with some practical tips.

Visualization

“The science of visualization is kind of all over the map, but anecdotally and instinctively it seems to make sense,” says Coyle. On this blog, we have a lower bar for science. We ask, “does this help me?”

Scott Adams took this approach with affirmations. If there’s something to this, Adams recalls telling himself, and I don’t use it that would be foolish. Dan Buettner and Dave Asprey thought the same thing about food.

Whatever it is, test it on yourself. If it works, you don’t need to worry about why.

Take a nap.

Sleeping is great, no one would argue that. Why though? Coyle says that professional athletes are great at sleeping. It makes sense for them, they’re up late to compete. What can you and I do?

Barbara Oakley explains in her book, A Mind for Numbers, that our brains need sleep to organize what we learned. Imagine what a store looks like after the first holiday rush or when college students return to town. It’s a mess. At night the store gets restocked, the second wave of toys is brought out, and the floors get cleaned. That’s what happens in our brains as well. Everything we learned gets put in a place.

Reframe repetitions

Our slow moving bear with a telescope needs a lot of practice. That can get boring, if you let it. Coyle says that you need to reframe repetitions. Rather than conjure up drudgery, says Coyle, take a moment to embrace the beauty in doing the same thing over and over.

Be patient while doing good work.

It takes time says Coyle. It took Stephen Dubner years to write a great book. It took Chris Hadfield years to become an astronaut. It took Gary Vaynerchuk years to create a business.

You have to know this, and at the same time do your best work. Your best work, Austin Kleon notes, will be far from the work of people you admire, and that’s okay.

Have a gardener and carpenter mentality says Coyle. Be patient like a gardener, who knows that seeds don’t sprout the next day. At the same time you should do your best work so that when the harvest comes, you have built something that will stand the test of time.

Feel stupid.

“Don’t be afraid of feeling stupid,” says Coyle, “that’s where the good stuff happens.” Feeling stupid is part of stretching, of getting out of a bed that’s too soft and into one that’s just right. But you don’t need to walk around and aim to be stupid. Naveen Jain says that he reads widely so that he can ask second level questions. If you approach an expert, Jain says, they’ll probably dismiss you if you ask something elementary. But, if you ask something a bit above that, they’ll engage with you more. You can be stupid on that level, knowing that you stretched to get there.

–

Thanks for reading. I’m @mikedariano on Twitter.

Wow, you made it to the end of the post. A solid 2300 words. That’s like 10 pages in a book (and forever online). If you found a few things valuable, you can donate $2.

[…] you want to be great at something, Dan Coyle said, you need to be around other people. Coyle calls them “hotbeds.” Austin Kleon calls them a […]

LikeLike

[…] may not be part of believing, but it may be part of achieving. In his book, The Talent Code, Dan Coyle noted that many people succeeded in “hotbeds.” His book begins with the story of a Russian […]

LikeLike

[…] on part of his career, it involves other people. This is true for Jamacian sprinters and Russian tennis players and comedians – groups are better to grow […]

LikeLike

[…] Dixon reframes startups as a maze. Dan Coyle reframes exercise repititions as meditative. Stephen Dubner reframes himself in situations to think […]

LikeLike

[…] Dixon reframes startups as a maze. Dan Coyle reframes exercise repetitions as meditative. Stephen Dubner reframes shopping experiences so he’s […]

LikeLike

[…] Megalis did it. Austin Kleon suggests you do it too. Penn Jillette did it at clown college. Dan Coyle calls them “hotbeds.” Judd Apatow works with a long list of people because they make him […]

LikeLike

[…] the problem by pretending her company is public. Chris Dixon reframes startups as a maze. Dan Coyle reframes exercise repetitions as meditative. Stephen Dubner reframes shopping experiences to change […]

LikeLike

[…] amount will get lucky and we all will be better for it. We benefit from the risks people like Dan Coyle take in writing books, David Chang take in opening restaurants, and Alex Blumberg take in starting […]

LikeLike

[…] tale terms as overnight success. Neither exists. Talent, like flowers, requires a garden to grow. Dan Coyle pointed out that you need to have the right setting (even if it’s just a “penniless […]

LikeLike

[…] that reward you are hard, but not too hard. Dan Coyle found the sweet spot in athletics. So too did Steven Kotler. Austin Kleon pointed out that his […]

LikeLike

[…] pretending her company is public rather than private. Chris Dixon reframed startups as a maze. Dan Coyle reframed exercise repetitions as meditative. Louis C.K. thinks of skills as merit […]

LikeLike

[…] Dan Coyle‘s work is the best I know on this idea of being around good people who can challenge you. […]

LikeLike

[…] Dan Coyle‘s research suggests a success rate between 50 and 80 percent. Steven Kotler has thoughts on this too. […]

LikeLike