This post is available in podcast form. Search “Mike’s Notes” in your favorite player. The audio version includes Metallica, and audio of the block quotes below. It’s on Soundcloud too.

Stop now if you don’t want to read another post centered around Michael Mauboussin. I’ve written about his podcast interviews three times(!!); Michael Mauboussin, Michael Mauboussin 2, & Michael Mauboussin 3. I think my 1990’s Van Halen collection had fewer editions.

After Tren Griffin‘s post about The Success Equation I knew it was time to finally read Mauboussin’s work rather than hear him talking about it.

The book was great. It explained concepts just as clearly as he does in these interviews. The part of the book that had the biggest effect on me was the Two Jar Model.

By FiveRings at English Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0, Link

That idea is that any outcome is a combination of “valuable” skill and “boost/drag” of luck. In the book Mauboussin uses ample examples, so I will too.

On Sunday afternoons our YMCA has tennis lessons. I get the kids in the car, pull out the driveway, pull back in because we don’t have our rackets, leave again, drive to tennis, get out of the car, and get the kids in their groups. As I sit there waiting and reading, none other than Serena Williams shows up (she’s visiting family) looking for a volley partner. I volunteer, of course.

We warm up. Williams, impressed by my forehand, suggests we play a friendly game. I agree, of course. My serve.

My first toss is just right (skill +10, luck +2) and with a pedestrian pace the ball glides across the net, into the service box. Williams steps into a backhand (skill +70, luck +5) and smashes a winner down the line. As I retrieve the ball I wonder if Elon Musk has talked to Williams about certain aspects of escape velocity.

Love, fifteen. Of course.

My next service toss is a little low and a wind gust pushes the ball a hair (skill +6, luck -2). This serve, a cumulative “4” does no better than the first. After hitting her winner Williams walks to the net and says something to the effect of “shoulder rehab” and “left handed.” The match continues.

In this parable, no cumulative score of my skill and luck is enough to win a point against Williams. Tennis is a game of skill. Now imagine instead of playing Tennis I’m managing a soccer team. Soccer is more toward the luck end of the spectrum and if I were to go against the greatest manager in the world, the chance of me coaching to a victory is much better, though still not good.

Mauboussin writes that we draw from each jar and the sum of the scores is the outcome. Sometimes we’ll be lucky and good, sometimes we’ll be bad and unlucky. Often we’ll be in the middle.

Before dive deeper, let’s dismiss platitudes available on motivational posters. Mauboussin writes, “There is no way to improve your luck because anything you can do to improve a result can reasonably be considered a skill.” That is, you don’t make your luck.

When Bill Gurley became an analyst he was lucky because soon after he arrived, the people above him left, there’s nothing he could do to improve that result. Gurley got a vacated position because he was skilled enough to prepare for and apply for it.

Often it’s hard to identify where on the spectrum we are. “Most of the successes and failures we see are a combination of skill and luck that can prove maddeningly difficult to tease part,” Mauboussin writes.

So what? Depending on the location, processes differ. For activities with more skill like surgery, games of checkers, tennis.

- “You can rely on specific evidence.”

- “History is a useful teacher.”

- Small samples are okay.

- Deliberate practice and checklists work.

For activities with more luck, like roulette or the stock market.

- Beware of small sample sizes.

- Fast mean reversion.

- Base rates are a better guidance.

Mix all these ingredients and you get a pair of suggestions for how to act in certain situations.

- Toward the skill end of the spectrum, use deliberate practice.

- Toward the luck end of the spectrum, focus on the process and not outcomes.

Example 1: Bill Belichick

Process. Football, Mauboussin writes, has a luck factor somewhere between hockey and baseball. It’s about 48% luck. I’m unaware about how much Belichick knows this but he seems to understand it. His process towards luck is to focus on what his players are doing, not the score. Belichick looks at how his team is playing, even when they’re losing. (4:30)

“I really felt good about the team, even though we’d gotten smashed. I felt something about the team that night in the second half that I really thought we could build on. Anyone that wanted to cash it in could have cashed it in. We weren’t going to win. We were behind, we were on the road, their crowd was in a frenzy. The Chiefs were playing very well but I could see the fight.”

Practice. In this clip, Belichick and his staff are explaining how they prepared for the play that would end the Seahawks season in Super Bowl 49. (35:00)

For the Patriots successful season there was both luck and skill. Belichick focused on the process parts where luck ruled the outcomes and was focused on the skill parts with specific practice.

Example 2: Stephen King

Process. No one knows what will be a bestseller, not even Stephen King. He told Rolling stone his best book was, “Lisey’s Story. That one felt like an important book to me because it was about marriage, and I’d never written about that. I wanted to talk about two things: One is the secret world that people build inside a marriage, and the other was that even in that intimate world, there’s still things that we don’t know about each other.”

Writing a bestseller has a fair bit of luck so King trusts the process. He focuses on the things he can do. King jokes that he only takes off three days a year (Christmas, July 4th, his birthday) because it makes for good copy. He really doesn’t. “The truth is that when I’m writing, I write every day.” Stephen King doesn’t know if a book will be a bestseller, but he knows the kind of work that he needs to do.

Practice. When King was interviewed about learning the rules of grammar he said.

“When we name the parts, we take away the mystery and turn writing into a problem that can be solved. I used to tell them that if you could put together a model car or assemble a piece of furniture from directions, you could write a sentence. Reading is the key, though. A kid who grows up hearing “It don’t matter to me” can only learn doesn’t if he/she reads it over and over again.” That’s part of the skill of writing. Understanding the building blocks of language.”

There are things a writer can control. In all the interviews of Mauboussin I’ve never heard him mention his writing process (beyond a preference for physical over digital books) but he has something like King identifies. I have a hex wrench and Ikea bookshelf. Mauboussin is on This Old House.

Example 3: Louis CK

I’ve written (long) notes about how Louis C.K. made Horace and Pete and there were parts of that story that fit this process and practice view that the two jar model suggests.

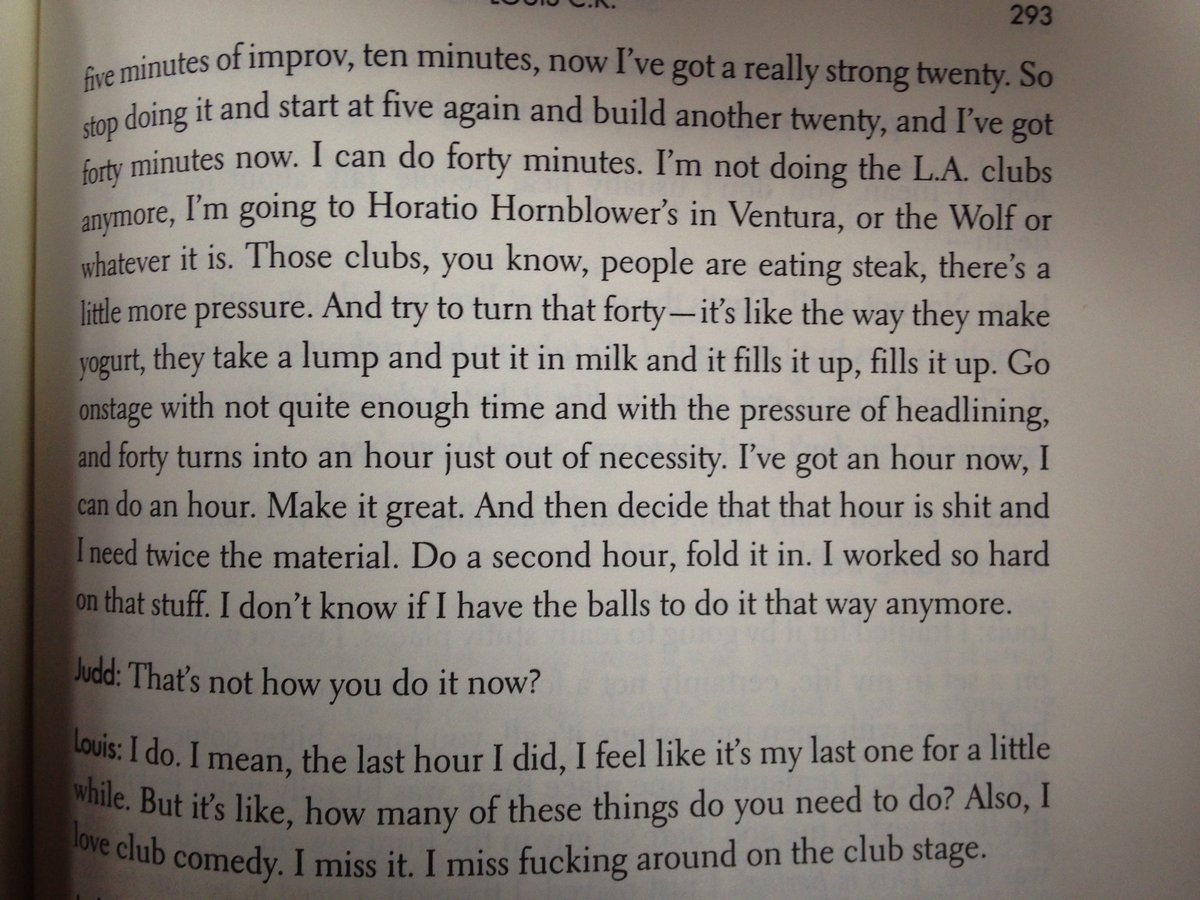

Process. If Stephen King doesn’t know what makes a bestseller, that means nobody does, Louis included. King writes daily, uncovering the story like a fossil, and stays true to the characters (“no kid ever ran to his mother and said that his sister just defecated in the tub”) . Louis told Judd Apatow that he too has a process for making comedy.

Start with five minutes, make it ten, stretch it to twenty, rinse, repeat. The outcome for “what’s funny” draws from the luck jar just as “football win” and “best selling book” draw from two jars as well. Each person though emphasizes the work that could lead to good results.

Practice. Here is part of an interview Louis gave with Charlie Rose when he was promoting Horace and Pete (lightly edited):

Charlie Rose: Here is what I hear. I mean, you know, write standup the best. Acting and getting — not only good reviews but also more and more roles. You’re now a director….You are now a producer…You manage this whole thing….I mean, do you come to some sense, I can pretty much do whatever I want?

Louis C.K.: Well, there are a million things I can’t do yet, but thank God, you know. You want to be able — you want to keep trying — you want to get — it’s like if you are in the army, a friend of mine was in the army back in the ’80s.

Louis C.K.: Late ’80s. And so, he’d just go to like, he took his little platoon, he’s sergeant, he’d go like, let’s go to jump school.Let’s all just go to jump school. And they go for, he was a, what do you call it, reserve.

Louis C.K.: So, on his weekends, instead of sitting around playing ping pong, let’s go to jump school. And then they have a patch for jumping. And then they go hey, let’s go to medic school. So, they all got rated as medics. And they got this big bunch of patches all these things skills that he’s packing his head with. Unfortunately, then a war broke out and he was sent right to the front. Look at all these skills you have.

Charlie Rose: And we need you.

Louis C.K.: I like being patches, it’s like being a boy scout. And then all of a sudden you can do that. You know, like what’s the movie, “Matrix.”

Charlie Rose: “Matrix,” yes.

Louis C.K.: When there is a helicopter and he says to her, you know how to play helicopter. And she goes wait a minute and she loads the program. Now I do. Well, anyone can do that. It just takes longer. You can just load a program. So, now I know how to create a multicamera drama and mount it the same week that I shot it. And how to direct many great actors which I had never done before.

Everything we do has some mix of skill and luck. Any little thing you can do is skill, and you should use deep work to get better at that. Any thing you can’t control is luck, and you’ll be well served to focus on good process rather than outcomes. Any outsized returns are a combination.

After the 2015 NBA finals Zach Lowe wrote:

“Yep, the Warriors got lucky. They suffered no major injuries, beat teams that did, and got through the West without facing the Clippers or Spurs.

Guess who else got lucky: every team to ever win the championship. Pick any playoff season — literally, any season — and you’ll find multiple injuries that tilted the championship odds. Sometimes those injuries were minor — temporary dings to a few key role players. Sometimes they were career-threatening injuries to stars.”

Thanks for reading,

Mike

ps. If you want more, I wrote a book about Bill Belichick’s Red Teaming. It’s a mix of process and practice.

[…] best understanding for the role of luck comes from Michael Mauboussin‘s Two-Jar model. Everything we do is an outcome luck mixed with […]

LikeLike

[…] airplanes is a high skill (rather than luck) activity. It’s why checklists work. It’s why deliberate practice with feedback works. […]

LikeLike

[…] part of success is skill and luck and maniacs try to increase their skill as much as possible. Time is one way to quantify […]

LikeLike

[…] Luck. Amazon fits the two-jar model. There were high skill draws; Bezos is smart and relentless. There were also high luck draws. For […]

LikeLike

[…] Control what you can, and understand the roll/role of luck. […]

LikeLike

[…] It’s hard to say they did anything wrong. Luck, as Michael Mauboussin points out, is something you can’t control. Nasty Gal’s success and failures very clearly fit the two-jar model. […]

LikeLike

[…] Another was The Success Equation by Michael Mauboussin which introduced the two-jar model. […]

LikeLike

[…] bias is a pesky rascal until you anchor to the base rate. That’s a start. Then take the two-jar model and figure out if the thing is based more on luck or skill. If it’s more skill, you can move […]

LikeLike

[…] The two-jar model. I love the two-jar model and it fit perfectly as the theory behind one of Morey’s […]

LikeLike

[…] honest reflections. Both fund manager and retail founder admitted to a mix of luck and skil (the two-jar model […]

LikeLike

[…] on the two-jar model seems about […]

LikeLike

[…] quote addresses the two-jar model so well. Let’s summarize what Michael Mauboussin and Jackson […]

LikeLike

[…] writing “my naïveté went unpunished,” when it came to hiring a construction crew. The two-jar model notes that great success requires great luck and had this early break gone against Meyer […]

LikeLike

[…] the two-jar model reminds us to consider the skill involved too. Synder and Kroc excelled here too. Stacy Pearlman […]

LikeLike

[…] two-jar model is how Michael Mauboussin taught me about comparing luck and skill. We’ll only reiterate […]

LikeLike

[…] That’s not a lot. Gurley, it appears, is on the same path as Brent Beshore, look at many companies but be choosy with the ones you invest in. Looking at the list there are names you know (Tinder, Snap, WeWork) but also unfamiliar ones. Those other, mostly B2B focused enterprises, are intentional. Gurley said, “there’s a ‘hits’ dynamic to consumer startups. Even if you are a very successful repeat entrepreneur, you may head out to do the next one and fall flat on your face.”Consumer startups and enterprise startups have different arrangements of the two-jar model. […]

LikeLike

[…] of uncontrollable things and the only thing I could control was my work ethic.” He understood the two-jar model and did things that would increase the skill scores like; a Chase training program and working […]

LikeLike

[…] me’ phase. After that consider how much you can move the needle. It helps to understand the two-jar model and how much of results are luck and how much are skill. Then adjust the expected […]

LikeLike

[…] once but beyond that it didn’t do any good. We all have 168 hours each week, spend them on skill jar […]

LikeLike

[…] to an idea Michael Mauboussin wrote about this in The Success Equation. Mauboussin introduced the two-jar model as a way to think about […]

LikeLike

[…] Peta found “cluster luck.” If a team had especially good results with runners on base, they had cluster luck. He knew it was luck because the results didn’t repeat. He created his own two-jar model. […]

LikeLike

[…] of reasons to fail but one that’s always in your control is your efforts. That fits with our two-jar model. The second was to ask, ‘what am I working toward?’ Dogen recounts playing tennis with […]

LikeLike

[…] Two-jar model. Thrope has a TJM view of life. He wrote, “Chance can be thought of as the cards you are […]

LikeLike

[…] two-jar model is a way to think about outcomes as being skill or luck based. We can control both our domain […]

LikeLike

[…] two-jar model is a theory that says outcomes equal skill plus luck. Michael Mauboussin writes that if you can […]

LikeLike

[…] uses a two-jar model to explain the balance of skill and luck. Singh’s experiences articulated Mauboussin’s […]

LikeLike

[…] Build up your skill.In Mauboussin’s work, he uses the two-jar model to explain outcomes. While the luck jar is independent, the skill jar is entirely dependent on what […]

LikeLike

[…] early career is the success equation. He advocates for active serendipity at the end of the podcast and emphasized that yes, luck plays […]

LikeLike

[…] and Luck. The two-jar model is handy for identifying outcomes that tend toward luck and outcomes that tend towards skill. […]

LikeLike